By the Analytical Group of the Foundation for the Defence of Democracy in Central Asia (FDDCA)

Russia’s policy toward the countries of post-Soviet Central Asia (PSCA) is defined through two lenses: its own version of a Monroe-type doctrine (see The New Monroe Doctrine and the Future of Post-Soviet Central Asia) and the doctrine of the Russian World.

The first establishes the geopolitical framework in which, according to the Kremlin’s plans, PSCA states should exist — above all through Russian military presence in the region and the prevention of their participation in military alliances with other external powers (see Russian Military Presence in the States of Central Asia: Character, Causes, Threats and Prospects for Overcoming).

However, no less important for implementing this policy is the second element: keeping the peoples and societies of PSCA within a Russia-centered cultural and ideological space defined by the doctrine of the Russian World. The latter is intended to counter competing cultural and value concepts associated with other external centers, primarily:

- Western-centered (“pro-Western” in Russian propaganda terminology),

- Islam-centered (“Islamist” in Russian propaganda terminology),

- Turkic-centered (“pan-Turkist” in Russian propaganda terminology).

As its natural support base and carriers of the culture and values of the Russian World abroad, the Kremlin primarily views the so-called Russian-speaking population. This category includes both ethnic Russians and Russified members of other peoples who have assimilated either Russian-Orthodox or Soviet-Russian cultural values and orient themselves toward them and toward Russia as their stronghold.

It was precisely the manipulation of the “Russian-speaking population” card that became a tool for launching wars against Ukraine, earlier against Moldova in Transnistria, and potentially could be used in the future against the Baltic states.

At first glance, such a risk may appear minimal for PSCA countries, where in the post-Soviet period the share of the Russian-speaking population declined to roughly 5% of the total population — about 4 million people out of roughly 80 million.

This is only partly true and only in comparison with the aforementioned regions. In reality, the Russian-speaking factor in PSCA states continues to be used by the Kremlin to promote the influence of the Russian World and, in certain cases, could serve as a tool of destabilization or even a pretext for military intervention.

Demographic Dynamics and Territorial Distribution

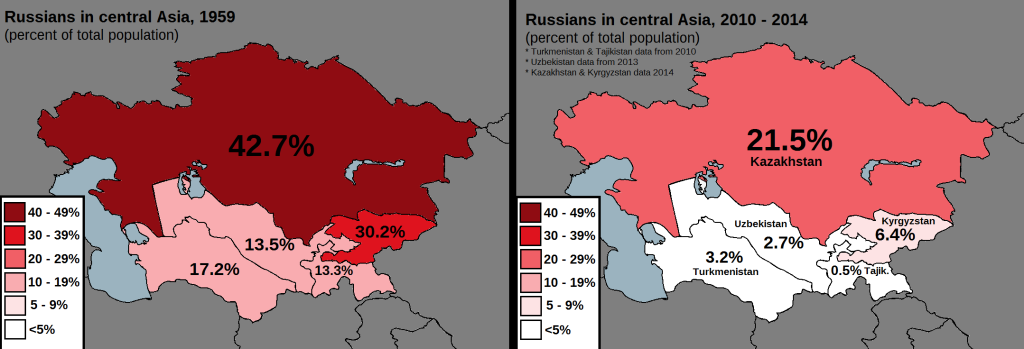

Most present-day PSCA territories fell under Russian colonial rule only in the 19th century and underwent intensive demographic colonization in the 20th century. The peak occurred during the Stalin era, when in several republics or their regions Russian-speakers comprised one-third to one-half of the population — or even a majority, as in northern Kazakhstan.

In Kazakhstan:

- in 1959, “conditional Russians” constituted 42.68% of the population,

- in 1989, on the eve of independence — 37.82%.

In the northern and northeastern regions, Russian-speakers comprised about 55% of the population versus roughly 30% Kazakhs.

In Kyrgyzstan:

- peak share (1959): 30.2%,

- in 1989: 21.5%.

In the capital Bishkek (Frunze), Russian-speakers made up about 57% of the population versus no more than 25% Kyrgyz. In the Chui region they constituted roughly 32%, only slightly less than the Kyrgyz (about 45%).

Russian-speakers were traditionally fewer in the other three republics:

- Uzbekistan — 8.4%,

- Tajikistan — 7.6%,

- Turkmenistan — 9.5%.

However, capitals looked different:

- Tashkent — ~32%,

- Dushanbe — ~35%,

- Ashgabat — ~38%.

Moreover, Russian-speakers effectively dominated key sectors of public life (see Post-Soviet Tajikistan: From Colony to Nation).

Over three post-Soviet decades the balance shifted toward titular populations. Today Russian-speakers constitute approximately:

- Kazakhstan — ~15%,

- Kyrgyzstan — ~5%,

- Uzbekistan — ~2%,

- Tajikistan and Turkmenistan — under 1%.

Demographic and Political Potential

Despite demographic decline, the Russian-speaking population still matters for two reasons.

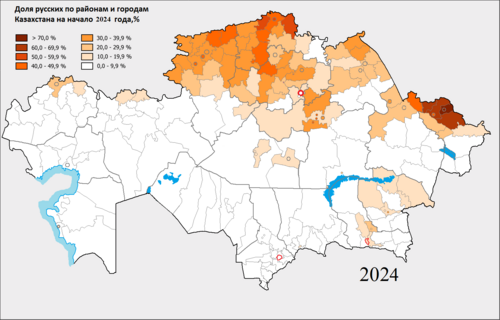

First, in Kazakhstan it remains significant due to concentration in northern and northeastern regions bordering Russia — from about 22% in Karaganda region to about 48% in the North Kazakhstan region, as well as about 30% in Almaty and around 20% in Astana. This makes it an important factor in determining Kazakhstan’s geopolitical future (see Kazakhstan Between Overcoming Colonialism and the Threat of Russian Revanchism).

Second, in Kyrgyzstan, although nationally reduced, Russian-speakers still comprise up to 35% of Bishkek’s population, a city that shapes the country’s political and cultural trends under the influence of Moscow’s “soft power” (see Kyrgyzstan: From the Main Democracy of Central Asia to a “Part of the Russian World”).

Together these two states largely shape PSCA’s future; therefore, the political dimension of the Russian-speaking factor must be examined.

Russian-speakers and the Russian World

Political loyalties of Russian-speakers are heterogeneous. Reliable survey data do not exist because:

- authoritarian environments prevent objective polling,

- many minority representatives conceal views or remain apolitical.

However, content analysis of blogs, interviews, and media suggests three broad orientations:

- Moderately loyal both to their state and to Russia/the Russian World.

- Strongly loyal to Russia and disloyal to their state.

- Loyal to their state and hostile to Russia’s policy and ideology.

The third group — the most promising for national development — is largely excluded from public representation. Consequently, only the first two groups appear in politics: conformist loyalists or openly pro-Russian actors. Kazakhstan illustrates this clearly.

The Russian Factor in Kazakhstan

Russian and Cossack movements posed a serious challenge to Kazakhstan’s territorial integrity already at independence.

- 1990–1991: mass separatist events in Uralsk.

- 1994: similar developments in Ust-Kamenogorsk.

Russia, then weakened, distanced itself.

Kazakhstan arrested separatist leaders:

- 1995 — Nikolai Gunkin,

- 1999 — Viktor Kazimirchuk group (12 members).

Authorities responded by promoting loyalist organizations representing Russian-speakers in public space — e.g., the Association of Russian, Slavic and Cossack Organizations. These groups publicly support Kazakh statehood and receive benefits.

Opposition groups (“Lad,” Russian Community, Cossacks of Semirechye) instead spoke of “discrimination” and “state Russophobia.”

While security services suppressed overt anti-state movements, social media revived such sentiments, especially after the Russia-Ukraine war, interpreted by pro-Russian residents as a step toward restoring empire and potentially annexing northern Kazakhstan.

Reliance solely on loyalist conformists cannot neutralize risks. Both loyalists and open nationalists:

- support bilingualism instead of Kazakh language transition,

- favor close ties with Russia,

- accept Russian-World historical narratives,

- orient religiously toward the Moscow Patriarchate.

Thus, substantively they differ little. The distinction is only rhetorical — open vs pragmatic expression. This creates a potential “Crimea scenario,” where even outwardly loyal actors could side with an occupying power.

The Need to Reformat the Russian-speaking Population

The goal for PSCA states is to detach Russian-speakers from Russia and:

- tactically disperse their ideological orientation toward non-threatening identities,

- strategically integrate them into civic nations.

Ethno-national dimension

- Re-nationalization of Ukrainians, Poles, Belarusians via diasporas.

- Redirect Cossacks toward anti-Moscow Cossack nationalism within decolonization movements.

- Support regionalist communities (Siberian, Ingria, Smolensk, etc.).

Religious dimension

- End identification of Slavs solely with Orthodoxy.

- Support Orthodox groups outside the Moscow Patriarchate.

- Encourage activity of Slavic Muslims within lawful frameworks.

Political and media dimension

- Shift audiences from Russian media to Ukrainian Russian-language media.

- Promote anti-Kremlin diaspora media.

- Create new Russian-language organizations loyal to their states and hostile to imperial policy.

Strategic measures

- Promote inclusive civic nationalism.

- Marginalize pro-imperial activists.

- Expand local language education programs for Russian-speakers.

Not Only a Threat but Also a Potential

Today, although many Russian-speakers remain pro-Russian, this is partly due to local authoritarian regimes that:

- failed to integrate them into civic nations,

- failed to create internal counterweights to the Russian World.

Changing this approach would allow full decolonization, marked by:

- integration of Slavic minorities into civic nations and bilingualism,

- marginalization and possible re-emigration of the most destructive pro-imperial elements to Russia.