Author: Sharofiddin Gadoev,

President of the Foundation for the Defense of Democracy in Central Asia

2 December 2025

Introduction

In the more than thirty years since the collapse of the USSR, Tajikistan has undergone a path rare for the region: from an attempt at a democratic breakthrough and civic mobilization to the consolidation of a personalist dictatorship rooted in the colonial legacy of the Soviet system and sustained by external support. Unlike other post-Soviet Central Asian states, Tajikistan has experienced neither a change of power nor genuine political renewal: one and the same regime, which emerged in the context of the civil war and the Russian hybrid intervention, succeeded in transforming itself into a stable autocracy.

This article examines Tajikistan as a typical product of incomplete decolonization: from the creation of the Tajik SSR and the artificial architecture of a “pseudo-national” state — through Perestroika, the awakening of civil society, and armed conflict — to the stage of “national reconciliation,” the subsequent purge of the opposition, and the “Turkmenbashization” of Emomali Rahmon’s regime.

The purpose of the analysis is to explain why, under these conditions, a full-fledged Tajik political nation never emerged; what mistakes led to the defeat of democratic forces in the 1990s; and which historical preconditions nonetheless create an opportunity for a national-democratic transformation of Tajikistan in the future.

- The Uniqueness of Post-Soviet Tajikistan

In its political history of the last three decades, Tajikistan is a unique country among other states of post-Soviet Central Asia (PSCA).

The PSCA states, throughout three decades of state independence, have been either stably authoritarian (almost all of them) or (relatively) democratic, like Kyrgyzstan (despite its recent downgrade in democratic ratings). And only Tajikistan ultimately became an autocratic state after the first years of struggle for a free society and several additional years of compromise between the regime and society.

Moreover, Tajikistan is the only PSCA state whose regime has been headed, from 1992 to this day, by the same dictator. In the post-Soviet space, there is only one more such country — Belarus, and this similarity is not accidental. It was precisely in these two countries that, at roughly the same time, two similar figures rose to power — Emomali Rahmon and Aleksandr Lukashenko — with comparable social and political biographies, embodying the same choice of development path for their respective states and supported by the same external power.

Even in such authoritarian regimes as Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan, their leaders have managed to change over the past three decades: in 2006–2007, 2016, and 2019 respectively, while in Kyrgyzstan as many as six presidents have changed. And only at the head of Tajikistan’s autocratic regime does one and the same person remain, embodying the neo-colonial, clan-based, and regressive path along which he and the forces supporting him have led the country.

It is therefore all the more important to understand what kind of path this is, how Tajikistan embarked upon it, through which stages it has passed up to the present moment, and at which crossroads it finds itself today.

- Tajikistan on the Eve of the Collapse of the USSR – A Colonial Formation

2.1. The History of the Tajik (A)SSR

It is impossible to understand the course of subsequent events in Tajikistan without understanding what the socio-political system of Soviet Tajikistan (the Tajik SSR) represented.

Despite their slogans about the right of nations to self-determination, the Russian Bolsheviks almost immediately re-created, in the course of the civil war, the Russian Empire in a new form — first as the RSFSR, then as the USSR. At the same time, their policy in the sphere of the national question was aimed at preventing the genuine revival and liberation of peoples from Russian colonialism, replacing it with the construction of something “national in form, socialist in content” (that is, Soviet-Russian). A part of this policy involved resisting national state-building and development where real historical prerequisites existed — among the European peoples of the former Russian Empire — and imitating this state-building among the peoples of the Islamic East, who had been developing according to another model.

The Russian Orientalist V. Bartold wrote that the national principle of territorial delimitation, which the Russian Bolsheviks implemented in Central Asia, was at that time entirely alien to local historical traditions. Today, the peoples of PSCA who have followed this path no longer have an alternative to the nation-state as the form of organization of the region’s basic political units (i.e. the respective countries). However, even with such a perspective, it is essential to understand that the delay in the consolidation of modern nations of the respective states is also a consequence of the fact that the Russian communists never set themselves the task of fully forming them, but rather engaged in an imitation of nation-building.

Tajikistan is the clearest example of the Soviet policy of pseudo-national construction. The republic began to take shape in 1924 (officially proclaimed in 1926), when a decision was made to divide the Turkestan ASSR along national lines. Given the ethnic intermixing of the Persian-speaking and Turkic-speaking populations of the region, united by a common Islamic identity and history, this very principle was deeply alien to the peoples of the region, and the formation of the territory of the Tajik ASSR on the basis of the lands of Eastern Bukhara and the upper reaches of the Zarafshan — beyond which major centers of Tajik settlement remained — undermined the development potential of the Tajik people.

In 1929, the Tajik ASSR was separated from the Uzbek SSR and turned into the Tajik SSR. By that time, the republic had been expanded by several districts (viloyats) from neighboring republics, which only partially compensated for the exclusion from the Tajik people’s developmental space of such major historical centers of Tajik presence as Bukhara and Samarkand (today uncontested territory of Uzbekistan).

And nonetheless, territorially, socially, nationally, and ideologically, the Tajik SSR (as indeed most other Soviet republics) was formed in such a way that it was incapable of national-state development independent of Russia.

2.3. The Colonial Structure of the Tajik SSR

It is cities — and especially capitals — that are the centers of modern nation formation. However, in Tajikistan during the Soviet period, its urban centers, including the capital, were effectively transformed into Russian (i.e. “Russian-speaking”) colonial outposts.

Despite the policy of Russian colonization of Turkestan during the Russian Empire, the territory of present-day Tajikistan was not significantly affected by it. Thus, in Khujand there were approximately 200–300 Russians; in Ura-Tube (Istaravshan) a few dozen; in the Panj region — only officers of the border guard; in the Pamirs — border posts and expeditionary units.

Large-scale resettlement of Russians/Russian-speakers into Tajikistan took place only in the Soviet period under the pretext of assistance from the Russian proletariat to the “backward peoples” of the East. As a result, by the end of Stalin’s rule (as of 1959), Russians/Russian-speakers constituted approximately half the population of Dushanbe (47.83%; by 1989, on the eve of the USSR’s collapse, 32.37%), more than a quarter of the population of Khujand (Leninabad) (27.76% in 1939), slightly less than a quarter in Qurghonteppa (Bokhtar) (18.6% in 1939), and a significant portion of the populations of Tursunzoda (Regar) and Nurek beginning in the 1960s and thereafter.

The distribution of social strata by ethnic composition is no less vivid an indicator of the colonial nature of the Tajik SSR. Thus, the Russian-speaking population in the Soviet period (in different years) constituted:

- 70–80% of engineers;

- 60–70% of teaching staff;

- 60–70% of medical personnel;

- 40–50% of the Academy of Sciences staff (by the end of the Stalin period — 70–90%);

- 20–30% of laboratory technicians, though they occupied most leadership positions.

In effect, during the Soviet period one can speak of the formation in Tajikistan of a socio-national system of a peculiar apartheid, in which cities became centers of the colonizers, while the local population was concentrated either in rural areas or in cities as second-class people. The only exception to this rule was a layer of Tajiks loyal to the colonial system, whose entry into this group required cultural Russification, and often mixed marriages with colonizers.

At the same time, colonial policy was directed against the national consolidation of Tajiks and the formation of a nationally-oriented elite.

2.4. The Containment of Tajik Nation Formation

The formation of a modern nation under conditions of external domination — and this was precisely the position of the Tajiks during the Soviet period — presupposes, among other things, two conditions:

- consolidation around a spiritual (ideological) system of values independent of the colonizers;

- intensive connections among different social and regional groups of the nation, through which they become more closely linked to one another than to external groups.

Even during the Soviet period, similar processes took place in many union republics. After the end of the period of Stalinist mass repressions, national intelligentsias began to revive, and the leadership of party organizations supported the national language and promoted national cadres, seeking to reduce dependence on Moscow.

In Tajikistan the situation looked different, in addition to the above-mentioned factors, also for the following reasons:

- in a historically Muslim people the nationally consolidating ideological factor was not so much secular national culture as religion, which was marginalized and effectively forced underground;

- the republic developed not a unified national but a regional-clan structure of society, which suited Moscow as an instrument for dividing the Tajiks — and this became one of the prerequisites of the future civil war.

Alongside the system of external (national) apartheid, a system of internal apartheid developed in the country, in which the governance of the republic in the interests of Moscow was ensured by representatives of the loyal Leninabad (Khujand) and Kulyab groups, whereby:

- the Leninabadis stood at the head of the highest republican nomenklatura;

- the Kulyabis formed the middle and lower levels of the republican nomenklatura, including power ministries, security forces, and economic managers;

- the inhabitants of the other parts of the country, including Garm and the Pamirs, were marginalized, and it was no accident that it was they who moved to the forefront of the anti-colonial modernization movement with the beginning of Perestroika.

3. Tajikistan During the Period of Changes that Began in the USSR (“Perestroika”)

3.1. The Awakening of Civil Society

The dismantling of the party monopoly in Moscow, which made possible the beginning of political changes in the USSR (the so-called Perestroika), opened the way for socio-political awakening in Tajikistan.

During this period, forces and tendencies that could not manifest themselves under the monolithic communist dictatorship began to appear clearly, namely:

- the forces of national revival and liberation — the movement “Rastokhez” (“Revival/Restoration”);

- the forces of religious revival — the Islamic Renaissance Party (after the collapse of the USSR — the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan, IRPT);

- the forces of civic renewal — the Democratic Party of Tajikistan;

- the forces of ethno-regional autonomism — advocates of Pamiri identity and autonomy within a unified Tajikistan.

It should be noted that, despite their different ideological vectors, all the above-mentioned forces acted together in seeking to transform Tajikistan into a modern, pluralistic country governed on the basis of representation of all major groups, their political competition, and cooperation.

This is critically important to emphasize, because regime and pro-regime propaganda (including Russian propaganda) has consistently sought to portray these forces as extremist, intolerant, Islamist, organizers of a “genocide of Russian-speakers,” and so forth. In reality, both initially and subsequently, all these forces — despite ideological differences — acted as a united front in the struggle for the renewal of the country, in which Tajik patriots stood together with Pamiri regionalists, Sunni Muslims (the so-called Islamists) with Ismailis, and the secular intelligentsia with spiritual leaders, and so on.

There was no “genocide of the Russian-speaking population” in Tajikistan — this is a myth unsupported by any facts. There was an exodus from a country engulfed in civil war (with Moscow’s participation) of part of the Russian-speaking population, alongside the forced displacement of more than one million Tajiks.

Thus, the civil war that later erupted in Tajikistan did not begin between democrats and Islamists, nor between nationalists and Pamiris — it began between all these groups of Tajikistan’s civil society, suppressed for decades, and the colonial establishment backed by Moscow.

3.2. The Reaction of the Colonial Establishment

Opposing the diverse forces of civil society that emerged with the beginning of changes in the USSR was the old nomenklatura, communist in form and colonial in content, oriented toward preserving both its own power and Moscow’s dominance.

It should be noted that while in a number of Soviet republics popular fronts emerged — becoming the basis for national consolidation, including parts of the national nomenklatura joining with the national public movement to achieve sovereignty — in Tajikistan the elite, colonial in its character and supported by Moscow, would create a Popular Front to counter the national movement.

But this would occur later. During Perestroika, the Leninabadi-Kulyabi establishment simply sought, through administrative and repressive measures, to preserve its monopoly on power and to prevent its democratization. Two of the most important milestones on this path were:

- the controlled and falsified elections to the Supreme Soviet in 1990;

- the controlled and falsified presidential elections in 1991.

These two reference points must be clearly noted in order to refute yet another pro-regime myth — that the civil war allegedly began due to an uprising of extremists against “legitimate authority.” In reality, the clan-based colonial nomenklatura, using administrative resources, did not allow genuinely competitive elections to take place nor the formation of a parliament reflecting the changing structure of society. Instead, it ensured for itself a monolithic majority in the so-called “legitimate structures of power” and elected its own president — Rahmon Nabiyev. The latter clearly chose a course of preserving the old order, the guarantor of which was to be the Russian occupation contingent, the so-called 201st Division.

At the same time as the leaders of other former Soviet republics — even those with a communist background — were seeking the withdrawal of Russian troops from their territories, the deliberate preservation of this force by the “legitimate authority,” combined with the authoritarian, anti-democratic nature of its formation, was the primary factor in the outbreak of civil war in the country.

- Russia and Tajikistan: “Anti-Maidan” and “Donbas” Technologies Against the Democratic Revolution

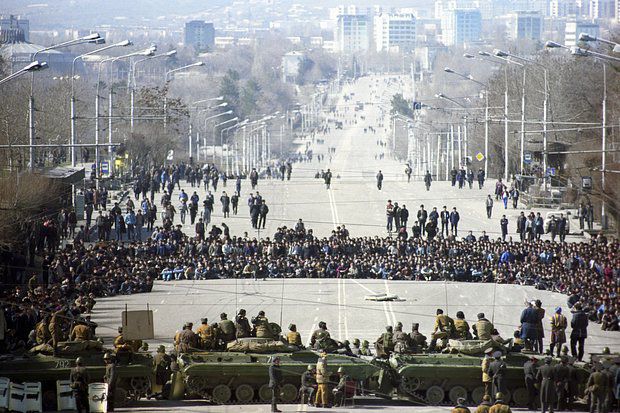

In the conditions of an authoritarian government’s unwillingness to engage in dialogue with the united forces of civil society, in January 1992 the capital city, Dushanbe, saw what was in fact the first — for that time — initially peaceful Maidan.

It should be noted that Tajikistan at that moment became an independent state de facto due, on the one hand, to the collapse of the USSR and, on the other, to pressure from civil society forces. At the same time, the group holding power was almost entirely oriented toward Moscow and, because of this, was unable to consolidate Tajik society.

Against the Tajik “Maidan,” the Leninabadi-Kulyabi group effectively began using classic “Anti-Maidan” methods — namely, transporting into Dushanbe their own titushki from the Tajik analogue of the Donbas of the Maidan period — Kulyab. This ended exactly as it did in Ukraine: in the spring–summer of 1992, the civil-society forces that had organized themselves in response took control of the capital and established their own government there.

Just as Yanukovych did in Ukraine, Rahmon Nabiyev effectively relinquished power (in Tajikistan he even formally resigned). However, instead of acknowledging the new realities — as happened in Ukraine with the Verkhovna Rada in 2014 — the Supreme Soviet relocated itself to the “Tajik Donbas,” i.e. to Kulyab.

What happened next in Tajikistan was, in essence, what Russia intended to do in Ukraine in 2014 but failed to achieve. Colonel Vladimir Kvachkov, who at that time commanded the Russian hybrid operation, publicly admitted in Russian media that Moscow had tasked him with overthrowing the new government in Tajikistan. As a cover for this, the so-called People’s Front of Tajikistan was created, headed by the criminal boss and warlord Sangak Safarov. In roughly the same period, Moscow used criminal groups led by the vor v zakone Jaba Ioseliani to overthrow the national democrat Zviad Gamsakhurdia in Georgia.

In reality, the seizure of Dushanbe in the autumn–winter of 1992 was carried out by the Russian “vacationers” (otpuskniki) of that time, for whose transfer and preparation the infrastructure of the Russian 201st base was used, with the active participation of Kulyabi titushki and other criminal elements. Russian military forces provided the reactionary forces with extensive support in combating the democratic forces, including artillery and air cover, the transfer of weapons and manpower, intelligence, and special operations.

The outcome of the so-called civil war — in fact a Russian hybrid intervention — was determined by the capture of Dushanbe and the central regions of the country by Russian troops and their proxies. After that, the conflict devolved into isolated pockets of resistance on the periphery of the country. This resistance was supported by no state, neither Western nor Eastern, while Russia operated in Tajikistan jointly with the Karimov regime, which had seized power in Uzbekistan and sought to prevent any “dangerous example” in a neighboring state.

It should be noted that during these events the colonial regime in Tajikistan was effectively rebooted. The Kulyabi security and administrative cadres came to the forefront, together with their new leader — Emomali Rahmon. In 1992 he was elected chairman of the Supreme Soviet, which had relocated to Kulyab, and in 1994 — president of Tajikistan, under conditions of an ongoing war in the country and blatantly falsified elections.

- “National Reconciliation” (1996–2001): An Operation to Neutralize the Opposition and Consolidate the Regime

Beginning with the first successful negotiations between the regime and the civic resistance, which had formed the United Tajik Opposition (UTO), a series of protocols and agreements were signed between 1995 and 1997, the main among which were the following:

- Protocol on the Basic Principles of Establishing Peace and National Accord in Tajikistan dated 17 August 1995;

- Protocol on Political Issues dated 18 May 1997;

- Agreement between the President of the Republic of Tajikistan, Emomali Sharipovich Rakhmonov, and the Leader of the United Tajik Opposition, Said Abdullo Nuri, following their meeting in Moscow on 23 December 1996;

- Protocol “On the Basic Functions and Powers of the Commission on National Reconciliation” dated 23 December 1996;

- Regulations on the Commission on National Reconciliation dated 21 February 1997;

- Additional Protocol to the Protocol “On the Basic Functions and Powers of the Commission on National Reconciliation” dated 21 February 1997;

- Protocol on Military Problems dated 8 March 1997;

- Protocol on Refugee Issues dated 13 January 1997.

These documents created the legal framework for what was declared to be a process of National Reconciliation and was intended not only to cease bloodshed and ensure the return of refugees, but also to begin the construction of a new nationwide socio-political system based on the principles of national accord, amnesty, dialogue, recognition, and inclusion of the opposition in governance.

It is essential to emphasize that the states participating in the negotiation process positioned themselves as de facto guarantors of the achieved National Reconciliation, the most important of which was Russia. It is not difficult to surmise that, in this case as well, Russia’s “guarantee” proved to be just as “reliable” as it was in the case of the 1994 Budapest Memorandum, under which, in exchange for Ukraine’s renunciation of nuclear weapons, it guaranteed Ukraine’s security and the inviolability of its borders. One should also note the continuity of Russian policy — under the documents on National Reconciliation stands the signature of Sergey Lavrov, then Russia’s representative to the UN.

Under the provisions of these documents, the UTO was allocated 30% of positions in the executive branch, members of its armed formations were to receive amnesty, they themselves were to be integrated into the Armed Forces of Tajikistan, its political parties were to have the opportunity to participate in elections, which were to be free and fair. Oversight of all this was to be carried out by the Commission on National Reconciliation and by the UN Mission of Observers in Tajikistan (UNMOT).

As a result, whether due to its political inexperience or to exhaustion of resources and the compelled nature of this reconciliation, the UTO lost already at the stage of signing this package of documents. Their norms and provisions were formulated as abstractly and non-bindingly as possible, including the absence of mechanisms for long-term guarantees of UTO interests, the failure to account for risks of violation of these conditions by the regime, and the lack of obligations on international guarantors (including those who might defend UTO, not only Russia) to respond to such violations, etc. In effect, already at the stage of preparation of these documents, representatives of the Russian diplomacy — experienced in such matters and guaranteeing the interests of the Rakhmon regime — outplayed the leaders of the UTO, who either could not, or no longer wished, to defend the interests of those who had entrusted them with representation.

The aims of Moscow and its protégé in Dushanbe in the operation titled “National Reconciliation” are evident from the manner in which it unfolded: the termination of armed resistance; the demobilization and fragmentation of its participants and leaders; the co-optation and corruption of its unprincipled segment and the elimination of the principled one (often those who initially seemed principled became unprincipled as their illusions gradually collapsed); and, ultimately, the consolidation of Rakhmon’s power over Tajikistan. All these aims were effectively achieved by the end of the first decade of the 21st century as a result of the following:

- the holding in 1999 of fully controlled presidential elections, in which 97.6% of the votes were attributed to Rakhmon, versus 2.1% attributed to the opposition candidate Davlat Usmon, as well as similarly controlled parliamentary elections, in which the Rakhmonist People’s Democratic Party of Tajikistan was allocated 36 seats versus 2 seats for the key opposition party — the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan;

- the termination in 2000 of the UNMOT mandate under the pretext that National Reconciliation had been successfully completed;

- Rakhmon’s subsequent refusal to preserve for opposition representatives the 30% quota, under the pretext that participation of political parties in government was now determined not by the conditions of National Reconciliation (“successfully completed”) but by election results (which he fully controlled);

- the removal from power of opposition representatives such as Ministers Mirzo Ziyoev and Zaid Saidov — the former subsequently killed in 2009 and the latter arrested in 2013;

- the dissolution of “integrated” UTO combatants throughout various branches of the army, with the elimination of disloyal figures and the full subordination of those who acquiesced (over time, the latter also became among the former, as happened with General Nazarzoda in 2015 and many others before him);

- the unwillingness of the leaders managing “reconciliation” on behalf of the UTO to respond in time to Rakhmon’s gradual seizure of full power, including due to the economic corruption of some and the political illusions of others (sometimes within the same individual).

6. The Crystallization of Rakhmon’s Dictatorship and the “Turkmenbashization” of Tajikistan

The dictatorship of Rakhmon, established with Moscow’s support, began to crystallize already in the first years of the 21st century and has continued to harden ever since. In addition to the developments already noted, the following key milestones of this process may be highlighted:

- Mahmadruzi Iskandarov, leader of the Democratic Party of Tajikistan and former head of “Tajikgaz,” who attempted to flee the regime’s repressions by escaping to Russia (the state — a “guarantor” of National Reconciliation), was detained in Russia in 2004 and, despite the absence of grounds for legal extradition, was abducted and secretly handed over to the Tajik authorities, who in 2005 sentenced him to 23 years in prison;

- the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan in 2015 was stripped of its registration and subsequently designated a terrorist and extremist organization; dozens of its members and leaders were arrested, including deputy chairmen Saidumar Husaini and Mahmadali Hayit (Chairman Muhiddin Kabiri left the country); both they and their relatives have been subjected to repression and torture;

- Umarali Quvvatov, businessman and leader of the opposition movement “Group 24,” was shot dead in Istanbul in 2015 after multiple attempts by the Tajik authorities to secure his extradition;

- General Abduhalim Nazarzoda, Deputy Minister of Defense and former commander of UTO forces, was killed in 2015 under circumstances that remain unclear — either in a coup staged by the authorities to eliminate him or in a forced uprising he initiated amid repression in the army against all individuals previously connected with the UTO;

- Since 2010, and especially after 2015, human rights defenders have recorded, in addition to domestic repression within Tajikistan, a growing number of extraditions and abductions of Tajik opposition figures, dissidents, and political émigrés in other countries, primarily in Russia;

- In 2012–2014, in Khorog, purges were carried out against Pamiri civic leaders and respected figures, and dozens of people were killed during these detentions;

- In 2021–2022, protests erupted in the Pamirs against the regime’s repressions, during the suppression of which security forces killed dozens of people, and hundreds more were subsequently subjected to repression.

7. The Present and Prospects of Tajikistan

Despite the accelerated “Turkmenbashization” of Tajikistan — with the establishment of dictatorship, a cult of personality around the leader, and the preparation of the ground for hereditary transfer of power to his son — the history of the past nearly four decades demonstrates that this is a country and a people with a profound internal demand for a modern, pluralistic socio-political system, a demand repeatedly manifested in the desperate struggle of its bearers against despotism.

There are many reasons why the forces of Tajikistan’s civil society did not succeed either in the 1980s or the 1990s: from the interference of external actors acting through local vassals, to the mistakes (not to say worse) of the leaders of the UTO itself.

However, from a historical perspective, and returning to the beginning of this analysis, the main reason lies in the fact that by the end of the Soviet period, in the colonial construct known as the “Tajik SSR,” Tajiks remained in the position of a colonized people rather than a fully formed modern nation with a national elite capable of defending its interests and possessing intensive internal ties and solidarity.

Although quasi-national state-building and delimitation were imposed on the Muslim peoples of Central Asia by colonizers in order to divide them and detach them from their civilizational roots, in the reality in which all neighboring states adopted the form of national states, the Tajik people also have no alternative but to complete the formation of their own political nation. And despite the historical resistance to this process by the colonial-despotic regime, today Tajiks objectively possess far more preconditions for this, namely:

- unlike the late Soviet period, several generations have now grown up for whom their country is Tajikistan, not the USSR;

- as a result of the war and subsequent devastation, Tajik cities ceased to be colonial outposts of the Russian-speaking population;

- first, refugee flows, and later forced mass labor migration, have smoothed regional differences among Tajiks, serving as an inoculation of a broader national consciousness;

- the regime itself, in order to legitimize itself within Tajik society, is compelled to promote not internationalist communism but — albeit deformed and caricatured — Tajik patriotism;

- despite the regime’s pro-Russian policy, the rampant anti-migrant and specifically anti-Tajik chauvinism in Russia contributes to the erosion of Russophilia among Tajiks and strengthens Tajik self-awareness.

All these are precisely preconditions — preconditions that the colonial-despotic regime prevents from maturing into the formation of a modern, fully developed nation, freezing Tajiks in a depoliticized, dignity-stripped, intimidated, and servile state that satisfies both the regime and its principal external patron. It is obvious that this situation can change only as a result of a national-democratic revolution — preferably peaceful and unifying for society.

However, given the history of the past decades, it is equally obvious that many obstacles and risks will stand in the way of such a scenario, and that the supporters of national-democratic transformation of the country already now need to analyze them and to develop a plan of subsequent actions in order not to repeat the mistakes of their predecessors.